Parallel Redundancy Protocol (PRP) is a method used in industrial networks to make sure communication never stops—literally never. Many systems around us depend on constant data flow to stay safe and reliable. Think of power substations, industrial robots, trains, chemical plants, and automated production lines. If the network drops even one message, things can go wrong or shut down.

PRP solves this problem in a very smart way: it sends every network message twice, at the same time, through two completely separate networks.

If anything happens to one of those networks—a cable breaks, a switch dies, someone unplugs something—communication continues instantly over the other network. There is no delay, no switching time, and no interruption. Everything keeps running smoothly.

This simple idea—duplicate every message—creates a powerful, seamless, and extremely reliable network that can survive failures without anyone noticing.

This article breaks down Parallel Redundancy Protocol in a clear, easy-to-understand way, covering its architecture, how the frames work, the types of devices involved, supervision methods, design rules, and practical tips for real engineering use.

Table of Contents

How Parallel Redundancy Protocol Works in a Simple Way

The basic idea behind PRP is surprisingly easy to understand. Instead of sending data through just one network, a PRP device sends the exact same message through two separate networks at the same time. These two networks are called Network A and Network B, and they must be completely independent so that a failure in one does not affect the other. The duplicate messages are identical except for a small tag added at the end that helps the receiving device recognize them as a matching pair.

When everything is working normally, both messages travel through their own paths and reach the receiving device at slightly different moments. The receiver always accepts the first message that arrives and simply ignores the second one when it shows up. Because this happens automatically and instantly, the application using the network never sees duplicates and never knows which network delivered the message. It just keeps receiving data normally, without interruptions or delays.

This straightforward duplication process gives PRP its incredible reliability. Communication never stops on either network, and the receiver always has two chances to get each message.

Why PRP Requires Two Independent Networks

PRP requires two networks that are truly separate. The idea is that each network should be able to function completely independently, and a fault on one should not affect the other. In practical engineering, this means that Network A and Network B should not share switches, cables, or power sources. They should ideally be placed in different physical paths. If possible, they should even be built using different hardware manufacturers so that firmware bugs or design flaws do not affect both networks simultaneously.

The independence of the two networks is the foundation of PRP’s reliability. If one network has a catastrophic failure—such as a complete loss of power, a failed switch, a massive broadcast storm, or a cable cut—communication still flows seamlessly through the second network. Because devices send data on both networks at the same time, and because the receiver always keeps the first frame it receives, the system never stops. Even if one network is completely destroyed, the other continues to perform efficiently.

Understanding Parallel Redundancy Protocol Devices

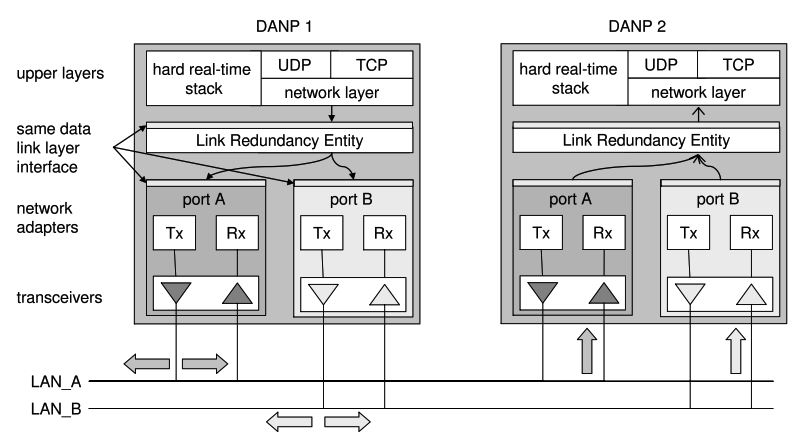

Parallel Redundancy Protocol relies on several types of devices, each playing a specific role in the redundant communication scheme. The main type is the Doubly Attached Node (DAN), which is a device that fully supports PRP. A Doubly Attached Node has two Ethernet ports, one for each network.

These devices include logic to duplicate outgoing frames, remove duplicates from incoming traffic, handle sequence numbering, manage supervision information, and coordinate with other nodes in the system. Most modern industrial devices designed for high availability support PRP natively. These include protection relays, PLCs, controllers, servers, HMIs, and industrial PCs.

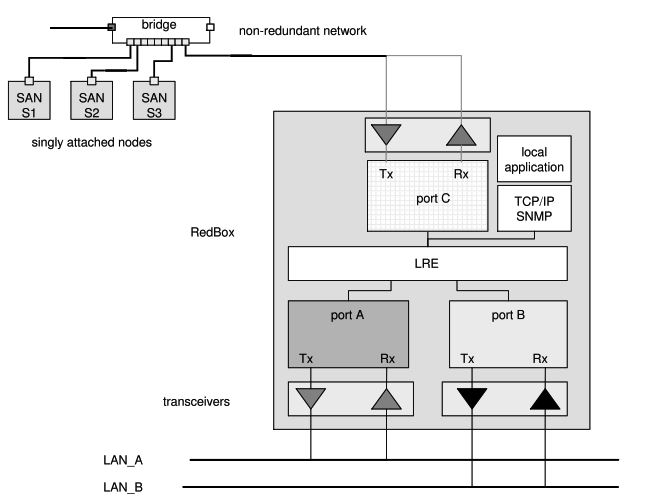

Not every device in a real-world system supports Parallel Redundancy Protocol. Many older or simpler devices have only a single network port and no PRP logic. These are known as Singly Attached Nodes. While they cannot participate in redundant communication directly, they can still be used in Parallel Redundancy Protocol networks by connecting them through a special device called a Redundancy Box, or RedBox for short.

A RedBox acts as a gateway between PRP networks and non-PRP devices. It takes single frames from SAN devices, duplicates them, and sends them across both networks (LAN A and LANB). Likewise, when receiving redundant frames, the RedBox eliminates the duplicate and sends a single frame to the SAN. This allows older devices to benefit from PRP even though they do not support it themselves.

RedBoxes must be placed carefully in network design because they handle additional workloads and maintain proxy entries for the devices they serve. Too many SAN devices connected to a single RedBox may overload it. However, when used properly, RedBoxes enable gradual migration to PRP and protect existing investments in legacy equipment.

The PRP Frame Trailer and How Frames Are Identified

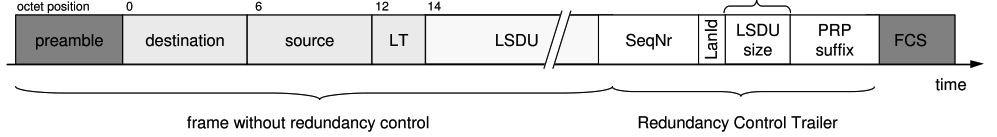

In a Parallel Redundancy Protocol network, every message is sent twice, one through each of the two independent networks. To help devices understand that these two messages belong together, PRP adds a tiny piece of information at the very end of each Ethernet frame. This small piece is called a Redundancy Control Trailer, and it works like a label that helps the receiving device recognize and sort the duplicate frames correctly.

The trailer contains two important things. The first is a sequence number, which is simply a number that increases with each message a device sends. If a device sends message number 105, both the copy on Network A and the copy on Network B will carry the same number—105. This makes it easy for the receiver to see that both frames are part of the same message pair.

The second thing inside the trailer is a marker (LanID) that identifies which network the frame came from. This helps the receiving device keep track of which network paths are healthy and which ones might be having trouble.

What makes the trailer especially clever is where it is placed. Instead of being inserted at the beginning—where switches might get confused—it is placed at the very end of the frame. Regular Ethernet switches do not look there, so they simply forward the frame without care or concern. This means Parallel Redundancy Protocol works smoothly with standard Ethernet equipment and does not require special hardware.

When a receiving device gets two frames with the same sequence number, it knows they are duplicates. It keeps the frame that arrives first and ignores the second one. Because the trailer provides the needed information to identify duplicates, the whole process is fast, automatic, and completely hidden from the application.

In short, the frame trailer is the tiny detail that makes the whole PRP redundancy process work. It allows devices to match duplicates, discard the second frame cleanly, and keep track of which network delivered the data. With this mechanism in place, PRP can provide seamless, continuous communication without requiring any special behavior from the rest of the network.

Supervision and Network Awareness

In a Parallel Redundancy Protocol system, devices need a way to understand the health of the two networks they are connected to. They also need to know which other devices are active, whether those devices are reachable through Network A, through Network B, or through both, and whether any part of the redundant path has stopped working. This is where the supervision mechanism comes in.

Every PRP device sends out small supervision messages at regular intervals. These messages are much lighter than normal data frames because their purpose is only to say “I am here, and I’m alive.” When another device receives one of these supervision messages, it updates its internal list of known devices.

This internal list is often called a Node Table, and it helps each device understand the current status of the entire PRP environment. The Node Table keeps track of which devices are reachable and on which network they can be reached. Over time, this table becomes a constantly updated map of the network’s health.

If supervision messages from a device suddenly stop arriving on one path but continue arriving on the other, the receiving device immediately understands that something is wrong on one of the networks. For example, if a device stops receiving supervision messages through Network A but still receives them through Network B, it knows that Network A has a problem. Even though communication continues flawlessly through Network B, this information is valuable for diagnostics and alarms. Operators can be notified that one part of the system needs attention, even though the application itself remains unaffected.

Supervision has another important role when dealing with legacy devices connected through a RedBox. Since these devices cannot send supervision messages themselves, the RedBox sends them on their behalf. This makes sure the rest of the PRP network still sees those devices as active and can treat them as part of the protected system. Without supervision, devices behind a RedBox would appear invisible or inactive, and the reliability of the network map would be lost.

The beautiful part of Parallel Redundancy Protocol supervision is that it does not affect performance or reliability. It runs quietly in the background while the main data traffic flows normally. Because PRP delivers data through two networks at once, supervision helps devices understand which path is currently healthy and which one may need repair.

Supervision simply provides awareness, visibility, and clarity so that engineers can understand what is happening inside the network and fix issues before they turn into real problems.

Parallel Redundancy Protocol and Flexible Network Topologies

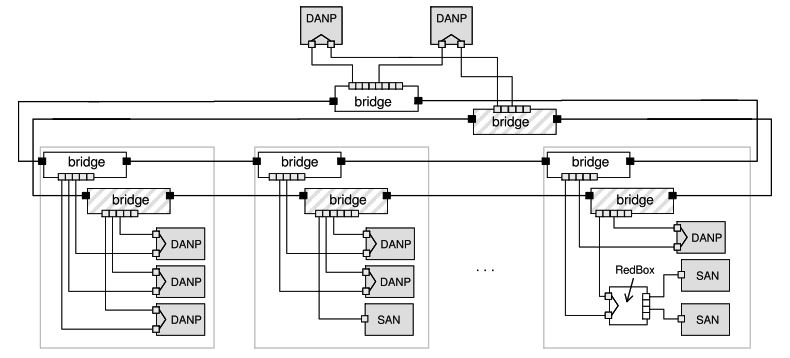

One of the reasons PRP is favored in industry is its flexibility. It places almost no restrictions on network topology. Engineers can design each of the two networks in whatever shape best suits the environment.

A star topology is often used in control centers, where numerous devices connect to a central switch. This topology is simple and effective for server-style architectures. In factory settings, ring topologies are popular because they minimize cabling and provide some additional resilience. Long production lines may use linear or bus topologies, stringing switches along a physical path. Highly critical systems may employ mesh networks to ensure the highest possible resilience.

Parallel Redundancy Protocol works with all of these designs. More importantly, the two networks do not need to match each other. One might use a star design while the other uses a ring. One might receive traffic from copper cables while the other uses fiber. One might be a high-speed gigabit network while the other operates at lower speeds. PRP welcomes diversity because it naturally reduces the risk of common-mode failures.

Migration Paths and Using Pre-Existing Equipment

Most existing industrial plants do not start with PRP. They often contain a mixture of new and legacy equipment. The introduction of PRP must therefore accommodate these devices. The most common approach is to use RedBoxes to allow older equipment to participate in the Parallel Redundancy Protocol network. Over time, more devices can be replaced with PRP-capable ones. As critical devices are upgraded, the redundancy of the system improves.

Eventually, as the majority of nodes become PRP-enabled, RedBoxes may be removed or used only for specialized equipment. A gradual migration path reduces cost, minimizes disruption, and allows step-by-step modernization. This method also allows testing and validation at every stage before fully committing to a complete PRP architecture.

Security Considerations for Parallel Redundancy Protocol

Parallel Redundancy Protocol provides availability, not security. It ensures data delivery even during failures, but it does not encrypt or authenticate messages. In industrial systems, security is essential. Firewalls, encryption technologies such as MACsec, segmentation using VLANs or zones, and intrusion monitoring should be added to Parallel Redundancy Protocol networks as needed. Many PRP deployments involve critical infrastructure, making security not just a good idea but a necessity.

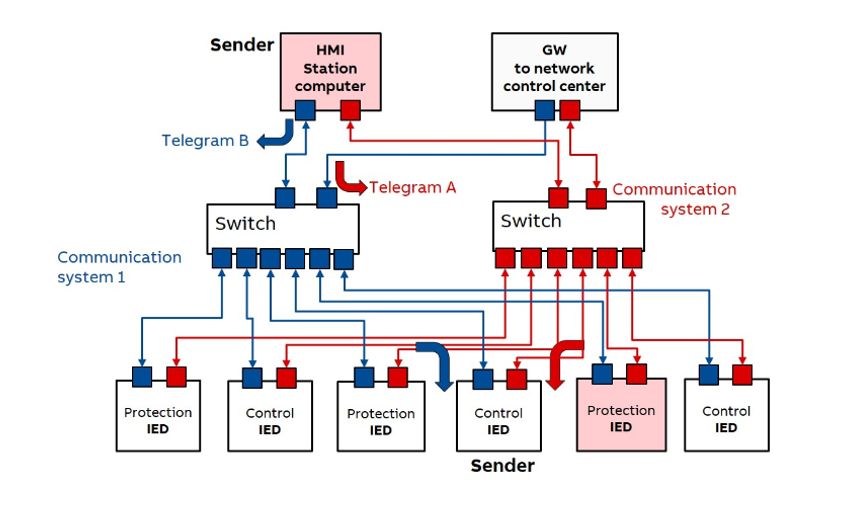

Understanding the PRP Network in the Diagram

The diagram shows how a Parallel Redundancy Protocol system uses two completely separate communication networks to make sure every message reaches its destination without interruption. The blue lines represent Communication System 1, and the red lines represent Communication System 2. These two networks run side by side but do not depend on each other. If one fails, the other continues working, which is the whole point of PRP.

At the top of the diagram, you see devices like the HMI station computer and the gateway to the control center. These devices act as senders. Each sender sends two copies of every message at the same time—one copy into the blue network and another copy into the red network. These messages are labeled “Telegram A” and “Telegram B” in the diagram. Even though they carry the same information, they travel through different paths to reach the receiving devices.

Both networks have their own switches, shown in the middle of the diagram. These switches forward the messages to the protection and control IEDs at the bottom. Each IED is connected to both networks, so it receives two copies of every message—one from each communication system. The IED keeps the first copy that arrives and ignores the second one. This is how Parallel Redundancy Protocol achieves seamless redundancy: the IED always has a second path available, but it never processes duplicates.

Because of this setup, even if a switch fails, a cable is damaged, or an entire network goes down, the devices at the bottom still receive every message through the remaining healthy network. Nothing changes from the point of view of the application. Communication stays continuous, stable, and uninterrupted.

In short, the diagram shows how Parallel Redundancy Protocol uses two independent networks, two parallel paths, and duplicate messages to guarantee reliable communication in critical systems like substations, factories, and industrial automation environments.

Conclusion

Parallel Redundancy Protocol offers one of the most dependable ways to keep critical communication running without interruption. By sending every message through two fully independent networks at the same time, PRP removes the need for switching, recovery, or failover. Systems continue working smoothly even when an entire network fails, which makes Parallel Redundancy Protocol a powerful choice for industries where reliability is not optional. Whether in power systems, automation, transportation, or any environment where downtime can lead to risk or loss, PRP provides a simple yet extremely effective foundation for continuous communication.

Understanding Parallel Redundancy Protocol also creates a natural bridge to the next major redundancy technology used in industrial networks: High-availability Seamless Redundancy, or HSR. While PRP relies on two parallel networks, HSR creates seamless redundancy using a ring structure without the need for separate network paths. If you want to explore how HSR works, how it compares to PRP, and when each method is the better choice, the next article dives into it clearly and simply.

Un excellent article 👏🏻 Merci pour cette explication claire et pédagogique du PRP. La manière dont tu décris les mécanismes de redondance, le rôle des différents nœuds et les avantages pour les réseaux industriels est vraiment éclairante.

Très utile pour tous ceux qui travaillent dans l’automatisation et l’énergie. Bravo pour la qualité du contenu 👏

Merci beaucoup pour ton retour, ça fait vraiment plaisir !

Je suis ravi que l’article t’ait été utile et qu’il apporte une vision plus claire du fonctionnement du PRP et de ses avantages pour les réseaux critiques.