Modern industrial networks depend heavily on remote communication. Whether it is a control center talking to a substation, a SCADA system collecting data from a water pump, or a utility monitoring dozens of remote field stations, the network path between these locations must be reliable, secure, and predictable. Two common technologies are used today to connect a central control system to a remote site: a site-to-site VPN tunnel and NAT port forwarding through a modem connected to a private APN.

Although both methods allow data to travel from the central system to a remote device, they behave very differently. Many communication problems—especially in critical infrastructure—come from misunderstanding this difference. In simple English, this article explains how each method works, why they behave differently, and why it matters so much when running SCADA protocols like IEC 104, DNP3, Modbus TCP, or IEC 61850.

Table of Contents

Understanding What a Site-to-Site VPN Really Does

A site-to-site VPN creates a secure, encrypted tunnel between two networks. One endpoint of the tunnel sits in the control center, and the other sits in the remote site—such as a substation or an industrial plant. Once the VPN tunnel is created, the two networks behave almost as if they are physically connected by a long Ethernet cable. Devices in the control center can communicate directly with devices at the remote site, using their actual internal IP addresses.

What makes a site-to-site VPN so powerful is that it is based on routing, not forwarding. This means traffic between networks follows proper IP paths, with each remote network announced to the VPN server. As a result, the control center gains full visibility of each remote LAN without needing NAT or port forwarding.

How Routing Works in a Site-to-Site VPN

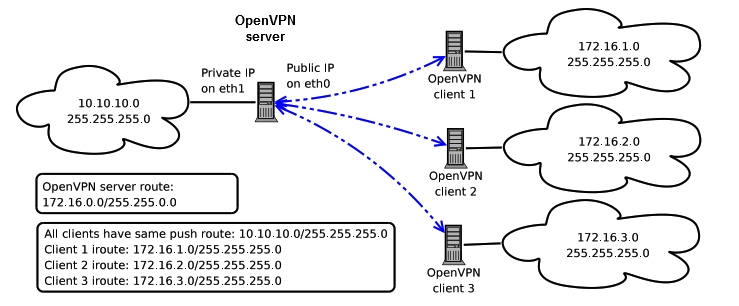

In a routed VPN setup, each remote site has its own subnet (for example, 172.16.1.0, 172.16.2.0, 172.16.3.0). The VPN server keeps routing rules that map each subnet to the correct tunnel. When the control center sends traffic for one of those networks, the server forwards it down the matching tunnel to the correct remote LAN.

Because the VPN provides true network-to-network routing, all traffic types — SCADA, engineering tools, SNMP, web interfaces, IEC 104, MMS, Modbus TCP — can travel across the tunnel without per-device configuration. The VPN is a full bridge between networks.

What NAT Port Forwarding on a Private APN Really Means

Now let’s consider the second common architecture: using a 4G or 5G modem connected to a mobile provider’s private APN. A private APN is not connected to the public internet, which gives some security benefits. However, most LTE/5G modems use NAT—Network Address Translation—instead of routing. The modem receives an IP address from the APN network, but all the devices behind the modem usually sit on a private LAN such as 192.168.x.x or 10.x.x.x.

Because of this, the control center cannot directly reach the devices behind the modem. Instead, the engineer must configure NAT port forwarding. For example, if the SCADA server needs to reach an RTU using IEC 104 on TCP port 2404, the modem must be configured to “forward” that specific port to that specific device. If another device—perhaps a relay, a meter, or a PLC—also needs remote access, more port forwarding rules must be added. And if an engineering tool uses dynamic ports or multiple connections, it may not work at all.

This is the key limitation of NAT-based communication: it does not give visibility into the remote network. It only allows the outside world to reach an internal device through a single port or small set of ports. There is no real routing between networks, only small holes in the NAT table that allow limited traffic. If the NAT table resets or times out, communication breaks. In cellular environments, this can happen often.

The Core Difference: Routing vs Forwarding

Everything ultimately comes down to one simple idea: a VPN routes networks together; NAT only forwards ports. Routing means both networks know how to reach each other. Devices can communicate freely using their actual IP addresses. NAT forwarding, however, is like punching small holes in a firewall and pointing each hole to a single device and a single port. You only get access to whatever the modem chooses to expose.

Because of this, a site-to-site VPN behaves like a proper network connection, while NAT behaves like a restricted doorway that only allows specific kinds of traffic through. This difference becomes critical when running SCADA protocols that expect stable, long-lasting, two-way communication.

A Practical Example to Make the Difference Clear

Consider a substation that contains several devices: an RTU, two protection relays, and a meter. All of them sit on a local network, for example the subnet 192.168.1.0/24.

If the site is connected using a site-to-site VPN, the control center can access everything naturally. The SCADA server can talk to the RTU. Engineering software can connect to the relays. Meters can be read over Modbus TCP. SNMP monitoring works. Pings work. Web interfaces of devices can be opened without obstacles. The control center sees the entire substation LAN exactly as it is.

But if the site is connected using NAT port forwarding on a private APN, the control center cannot see the network at all. It cannot ping anything. It cannot browse or scan. It cannot discover devices. It can only talk to the devices for which a specific port forwarding rule has been created. Want to access the RTU using IEC 104? Forward port 2404. Want to access a relay’s web interface? Forward port 443. Want engineering access? You may need dozens of ports—and even then it might still fail because the relay may use dynamic or temporary ports that NAT cannot handle.

This is why NAT connections often feel “blind,” whereas VPN connections feel “transparent.”

Security Differences Between VPN and NAT

Another major difference lies in security. A site-to-site VPN encrypts all traffic between the control center and the remote site. Both sides authenticate each other, ensuring that only trusted devices can establish the tunnel. Firewalls can inspect and filter traffic based on the real IP addresses of devices. Security teams can monitor the network for suspicious behavior. This creates a strong and predictable security model.

NAT on a private APN, however, provides no encryption at all. The private APN protects the devices from the public internet, but the communication between the control center and the modem is still unencrypted unless the SCADA protocol itself uses encryption (which many do not). NAT also hides the internal devices, which helps somewhat, but it also prevents proper monitoring and makes security auditing more difficult. If a device inside the APN becomes compromised, NAT offers no real protection.

VPNs also integrate better with cybersecurity tools such as IDS/IPS systems, network firewalls, and event monitoring platforms. NAT-based connections offer none of this visibility.

Why Many Projects Choose NAT Despite Its Limitations

The main reason engineers choose NAT through a private APN is cost and simplicity. It is much cheaper to deploy a SIM card with a simple LTE modem than to install a proper industrial router capable of site-to-site VPN functionality. NAT also seems easier because it requires less configuration—just forward the port you need, and the system works.

However, this simplicity comes at a cost. Many organizations later discover that they need remote engineering access, firmware updates, diagnostic tools, security monitoring, or more reliable SCADA communication than NAT can handle. At that point, they must replace the NAT system with a VPN system, which results in extra work and additional cost. NAT often works for small, single-device sites, but it does not scale well and cannot support complex industrial communication.

Choosing the Right Method for Each Situation

When reliability, stability, and long-term maintainability matter, a site-to-site VPN is almost always the proper solution. Substations, gas pressure stations, water facilities, and other critical infrastructure require secure and predictable communication. VPNs provide the transparency and flexibility needed to maintain these systems safely.

NAT with a private APN may still be acceptable for small, simple sites where only a single RTU needs to send basic telemetry, and where engineering access is not required. In these cases, the lower cost and simplicity may justify the choice. But for anything larger or more critical, NAT becomes a limitation rather than a convenience.

Conclusion

The main difference between a site-to-site VPN and NAT on a private APN is this: a VPN connects two networks completely, while NAT only forwards specific ports to specific devices. A VPN gives full access, stable connections, proper routing, and strong security. NAT gives limited access, unstable behavior for certain SCADA protocols, and very little visibility into the remote network.

When you need a robust, scalable, long-lasting communication link—especially for IEC 104, IEC 61850, or engineering access—the correct choice is almost always a site-to-site VPN. NAT should be used only for very simple or very small setups where full functionality is not required.